Post by Andrei Tchentchik on Jun 24, 2019 16:20:42 GMT 2

(.#218).- The first traces of the Higgs boson.

The first traces of the Higgs boson.

By Cyrille Vanlerberghe - Updated on the 26/07/2011 at 09:32

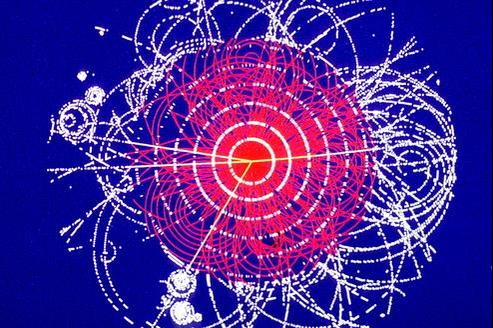

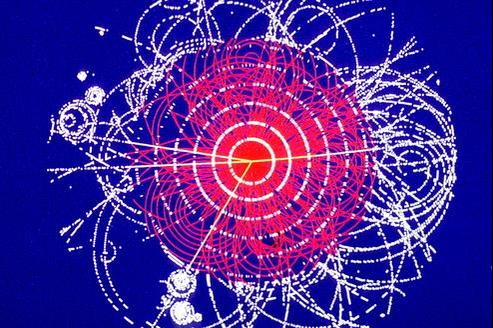

Simulation of the demonstration of a Higgs boson in one of the LHC detectors, which physicists use to project protons against each other.

The new CERN accelerator, the LHC, may have seen the first signs of an elusive particle called "Higgs boson".

"It's been ten years since I was so excited at a physics conference," admits with a broad smile a French researcher in the corridors of the great European conference of particle physics in Grenoble. The cause of all this excitement and lively debate on the sidelines of the presentations is the discovery by the LHC, the new particle accelerator Cern in Geneva, signs that could be the first evidence of the existence of the boson of Higgs, the elusive particle that has been the absolute Grail of the discipline for years.

This particle will undoubtedly be worth a Nobel Prize to its discoverers because, according to the theory imagined by the British Peter Higgs in the 1960s, it must allow itself to explain why all the particles that compose us, such as protons or the electrons, have a mass. The news is all the more exciting because after start-up problems, the LHC (Large Hadron Collider) accelerator now works perfectly and will allow European researchers to beat off their American colleagues, including the competing machine. , the Tevatron, arrives at the end of life and will not be able to discover the Higgs alone.

"I know it's difficult, but you have to be patient," says Rolf Heuer, Cern's managing director. He refuses, like his colleagues, to take the plunge and confirm the discovery of the Higgs boson, but his little smile still betrays his excitement. Despite this official caution, the curves presented Monday by the spokespersons of the two major detectors of the LHC, Atlas and CMS, are disturbing to say the least. The two scientific teams, each bringing together more than 3,000 physicists from around the world, have both found completely unrelated comparable disturbances in the same energy bands. In an area between 115 and 140 GeV (gigaelectronvolt, or a billion electronvolts), the data curves of the two experiments each have abnormal bumps that could perfectly match the signature of the Higgs boson.

Physicists do not really see the particles they are looking for, but they use the LHC to project protons at speeds close to those of light and produce billions of decays, some of which, very rare, will cause the appearance of a particular particle, the Higgs for example. "The difficulty is that we are not yet sure that the bumps in the curves are not the result of fluctuations or background noise produced by parasitic events," says Dave Charlton, one of the door - Atlas Experience Center working at the University of Birmingham. "We need more data, but we should definitely be fixed on the Higgs by the end of 2012," says Johann Collot, research professor at Joseph Fourier University, a member of the Atlas experiment and organizer of the conference in Grenoble.

F I N .

The first traces of the Higgs boson.

By Cyrille Vanlerberghe - Updated on the 26/07/2011 at 09:32

Simulation of the demonstration of a Higgs boson in one of the LHC detectors, which physicists use to project protons against each other.

The new CERN accelerator, the LHC, may have seen the first signs of an elusive particle called "Higgs boson".

"It's been ten years since I was so excited at a physics conference," admits with a broad smile a French researcher in the corridors of the great European conference of particle physics in Grenoble. The cause of all this excitement and lively debate on the sidelines of the presentations is the discovery by the LHC, the new particle accelerator Cern in Geneva, signs that could be the first evidence of the existence of the boson of Higgs, the elusive particle that has been the absolute Grail of the discipline for years.

This particle will undoubtedly be worth a Nobel Prize to its discoverers because, according to the theory imagined by the British Peter Higgs in the 1960s, it must allow itself to explain why all the particles that compose us, such as protons or the electrons, have a mass. The news is all the more exciting because after start-up problems, the LHC (Large Hadron Collider) accelerator now works perfectly and will allow European researchers to beat off their American colleagues, including the competing machine. , the Tevatron, arrives at the end of life and will not be able to discover the Higgs alone.

"I know it's difficult, but you have to be patient," says Rolf Heuer, Cern's managing director. He refuses, like his colleagues, to take the plunge and confirm the discovery of the Higgs boson, but his little smile still betrays his excitement. Despite this official caution, the curves presented Monday by the spokespersons of the two major detectors of the LHC, Atlas and CMS, are disturbing to say the least. The two scientific teams, each bringing together more than 3,000 physicists from around the world, have both found completely unrelated comparable disturbances in the same energy bands. In an area between 115 and 140 GeV (gigaelectronvolt, or a billion electronvolts), the data curves of the two experiments each have abnormal bumps that could perfectly match the signature of the Higgs boson.

Physicists do not really see the particles they are looking for, but they use the LHC to project protons at speeds close to those of light and produce billions of decays, some of which, very rare, will cause the appearance of a particular particle, the Higgs for example. "The difficulty is that we are not yet sure that the bumps in the curves are not the result of fluctuations or background noise produced by parasitic events," says Dave Charlton, one of the door - Atlas Experience Center working at the University of Birmingham. "We need more data, but we should definitely be fixed on the Higgs by the end of 2012," says Johann Collot, research professor at Joseph Fourier University, a member of the Atlas experiment and organizer of the conference in Grenoble.

F I N .